Peter Viertel - Born November 16, 1920 in Dresden, Germany. Died November 4, 2007 in Marbella, Spain.

Peter Viertel - Born November 16, 1920 in Dresden, Germany. Died November 4, 2007 in Marbella, Spain.

Peter Viertel - Born November 16, 1920 in Dresden, Germany. Died November 4, 2007 in Marbella, Spain.

Peter Viertel - Born November 16, 1920 in Dresden, Germany. Died November 4, 2007 in Marbella, Spain.

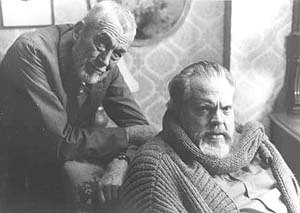

At Large With Huston and Hemingway in the Fifties

[Above] John Huston and Orson Welles

The section below is excerpted from Mr. Viertel's memoir Dangerous Friends: At Large with Hemingway and Huston in the Fifties. Copyright ©1992 Peter Viertel.

[I]t was high time I showed him the manuscript of my novel, even though I had not yet finished it. I called Jeannie Sims, his production secretary since the making of The African Queen and after checking, she asked me to visit John on the set the next day. The Moulin Rouge company was shooting in one of the big restaurants in the Bois de Boulogne, and I made my way there with a copy of my typescript in a manila folder.

On the set were scores of extras, a band, and a large crew, not an ideal locale for my visit, I thought as I was led by a uniformed guard to the center of all the activity. I greeted Jack Clayton, the unit manager, and Ozzie Morris, the cameraman, and then John appeared from behind the camera. "Well, kid, it's nice to see you," he said, chuckling to himself as he did whenever he was pleased to see an old friend. Hesitantly, I told him that I would like to have a word with him whenever he had a moment to spare, and he said: "What about right now?" He took my arm and walked with me to a quiet corner. "You're busy," I objected. "I'll wait until you break for lunch."

"They don't break for lunch in this country," he told me. "Go on. What's on your mind?"

"I've written a novel about you," I said. "About both of us, would be more accurate...."

"You have, have you, kid?" he replied. "Well, that's interesting." He seemed flattered and amused.

"I want you to read it," I went on. "If there's anything in it you don't like, I'll change it. And if you hate the whole thing, I won't publish it. If it really bothers you, I'll just throw it away."

"Nothing anybody writes about me bothers me, kid," he said, grinning. "You want me to sign a release? I'll sign one right now."

"I want you to read it. Whenever you have time."

"I'll take time," came the reply. "I'll start reading it tonight."

Behind us I could see the worried face of an approaching assistant director. Jeannie Sims was a step or two behind the man. "I think they want you back," I said, but Huston was unperturbed.

"Everything else all right?" he asked.

"No. Everything else is not all right."

He laughed. "I know what you mean, kid" was his only pointed comment. "I'll call you tomorrow after I've read your novel."

"There's no hurry."

"I'll call you tomorrow," he insisted.

He did call, surprisingly enough, or rather Jeannie did, on his instructions. Again I was summoned to the set, and again he abandoned his duties as a director without a moment's hesitation. He was enthusiastic in his praise, more so than he had ever been about anything I had shown him. I knew him well enough to realize that he was sincere. I had witnessed several occasions when his praise for another writer's work was meant to be an encouragement and nothing more. But that day his comments gave proof of a personal involvement in what he had read that went far beyond mere approval. "It's the best thing you've ever done," he said. "I'm proud of you, kid."

"Did it bother you?" I asked lamely.

"Sure, it bothered me," he replied, "and that's added proof it's good."

"Are there things in the book you'd like me to change?"

He laughed. "Don't be a horse's ass. Of course not," he said. "How does the story end?"

In a few sentences I described the ending I had planned. He listened attentively. "The director shoots an elephant, a cow," I told him. And the herd, led by three or four males, destroys a native village. The end is a total disaster for the natives that live in the village."

He shrugged. "Yeah . . . I suppose that's a pretty good ending," said. "But I feel it would be better if there was a personal disaster, the death of someone close to your hero that results from the shooting the elephant."

"The writer? The storyteller?"

He laughed. "Not a bad idea, but it won't work, as you well know. No, I was thinking that Kivu should die, the little black guy with the spear, the chief hunter. What do you think of that? It would have a greater effect on the hero of your piece, be more devastating for him."

It was an idea that had not occurred to me, but I knew immediately that he was right. "I'll try it," I said.

"You do that, kid. And then show it to me. Take your time. Don't be in a hurry to finish your novel. It's too good to foul up now."

"And you're sure you won't mind if I publish it?"

"That's a damn fool question if I ever heard one," he said. "Of course you're going to publish it. Why shouldn't you? That's why you wrote it, isn't it?" He gave me an affectionate hug. "Now I've got to get back to work, I suppose, although I'd rather spend the rest of the day talking to you about your book."

I drove back to the rue Spontini, and for the first time since we had moved into the small flat neither the noise from the passersby on the sidewalk outside my window nor the memory of the upsetting events of the past weeks disturbed my sleep.

Copyright 1992 Peter Viertel

[The novel discussed in this excerpt is, of course, White Hunter, Black Heart.

Site by

Erik Weems